If you are like most runners, your weekly endurance training program consists of about 50% low intensity runs and 50% at moderate/high intensity. Furthermore, if you are like 90% of runners, you’ve probably had at least one running related injury in the past year. This simple mistake of overdoing moderate and high intensity running is the common denominator for many overuse running injury.

Evidence has shown us time and time again that the vast majority of elite athletes do at least 80% of their training at a low intensity. With about 20% of training at medium to high intensity. For example, Tønnessen et al. (2014) looked at elite cross country skiers (XC skiers have the highest average VO2max, meaning they are endurance beasts). These cross country skiers complete 90% of their training time at low intensity (Tønnessen et al., 2014).

The idea of a predominately high volume, low intensity training program is not new. The “mostly slow” training style of legendary running coach Arthur Lydiard made running very high volumes (100 miles per week) normal for marathon runners. He proposed that speed work should be “lightly sprinkled” throughout a base of high volume low intensity training, with more speed work closer to the competition phase of training.

So why, with the majority of endurance athletes using the 80:20 approach, do most recreational runners insist on doing a significant amount of moderate intensity running?

Answer: Mostly because we don’t know any better.

I say “we”, as for many years I was guilty of this style of training too. It’s an easy trap to fall into. Slow training feels too slow, so we go a little faster. and we end up running most of our runs at a moderate pace. Unfortunately, running most of our runs at a moderate speed results in increased cumulative fatigue, which increases our risk of injury.

A more modern factor effecting recreational runners training intensity is the so called “Strava Effect”. That is, running faster than you usually would to rank higher on a “Strava segment”. Although Strava is a great way to record runs, it does lead us to become more competitive with our training, ultimately reducing our performance on race day.

Heart Rate Endurance Training and Rate of Perceived Exertion

So, you have realised you probably do most of your training too fast? Great! This is the first step to improving your performance. The next step is to put it into practice.

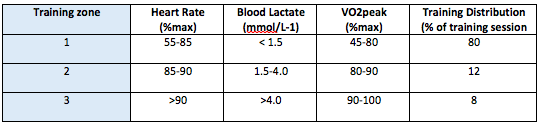

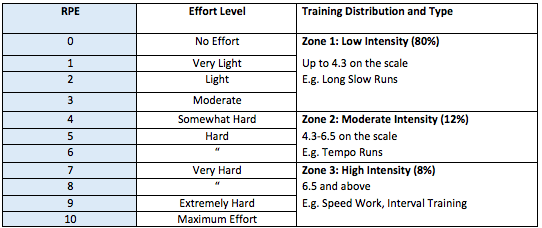

Below we have outline the different “training zones”, using rate of perceived exertion and % of HR max. We have also outlined how to tell if you are running too fast without using a heart rate monitor.

The two tables below outline the different “zones” of endurance training intensity in relation to heart rate and rate of perceived exertion (RPE). RPE is a scale from 0 – 10, where 0 is sitting on the couch and 10 is working as hard as you can possibly imagine. We prefer to use RPE rather than heart rate when determining how hard a workout is. This is because wrist heart rate monitors can be unreliable and heart rate can be influenced by other factors such as caffeine and stress.

Zone 1 (Slow runs)

These will comprise over 80% of your total training volume and are best run at “conversational pace” (A pace where you can have a conversation without hyperventilating, it’s your “go all day” pace. Running at this pace improves your general aerobic fitness as well as your bodies ability to tolerate the load of running long distances.

Zone 2 (Tempo Runs)

These are your “Threshold runs” or “Tempo runs”. This is a much smaller proportion of your overall training volume. Threshold runs are run at a “comfortably hard” pace, usually similar to an athletes 10km race pace, or 15s/km faster for well-trained athletes.

This type of running aims to improve lactate threshold and delay general markers of fatigue. However it is highly fatiguing and should comprise 5-10% of your total training volume.

Zone 3 (High Intensity Runs)

High intensity training. This type of training usually involves intervals of “all out bouts” of high intensity running, with rest breaks between each interval.

Read more about How To Nail Your Interval Training here.

The aim of high intensity training is to build on your base of high volume, low intensity training. It will help maximise VO2 Max as well as build strength endurance by recruiting less used muscle fibres. This type of training causes significant fatigue and comprises only a small portion (approx. 5-10% of your training volume)

Quick Tip

Two hours after each run, write down your rate of perceived exertion. If you use an online run tracker such as Strava, write your RPE in the description of the run. This will help you track how hard you are working how you have improvement. For example, over the space of 6 months your tempo 10km run at 4:30 min/km may reduce from a 7/10 RPE to 4/10 RPE.

References

Helgerud, J., Hoydal, K., Wang, E., Karlsen, T., Berg, P., Bjerkaas, M., Simonsen, T., Helgesen, C., Hjorth, N., Bach, R. & Hoff J. (2007). Aerobic high-intensity intervals improve V̇O2max more than moderate training. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 39(4), 665-671.

Tønnessen, E., Sylta, Ø., Haugen, T. A., Hem, E., Svendsen, I. S., & Seiler, S. (2014). The road to gold: training and peaking characteristics in the year prior to a gold medal endurance performance. PloS one, 9(7), e101796.